(Lecture delivered for Marjorie Evasco's Literature Seminar Class on Poetry and its Sister Arts, De La Salle University, October 2007)

Some of these thoughts that I will share with you today you might have read in my online journal or blog, but I will add a little bit of recent experience. I used to hesitate to use the word ekphrasis (I preferred “picture poem”), because it sounded Greek to me, and of course it is, but let us use it anyway. We could in fact use some technical help from antiquity, from people who came before us, in understanding many things that we are undergoing in the world today. And understanding especially art, or culture, or the creative experience, which many of us customarily ignore. Perhaps the world, in its passion for disintegration, could use a little creativity instead of rushing to ruin. But let us leave it at that for the meantime.

Let us proceed by example and discovery (or rediscovery), before we proceed to define ekphrasis.

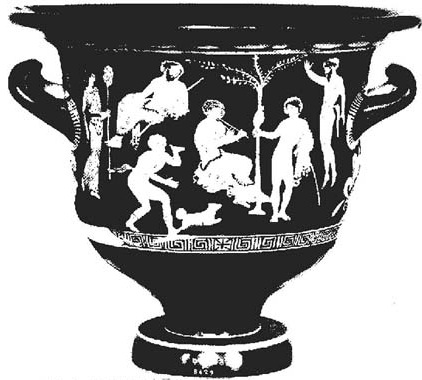

What are the ekphrastic poems that we know? We can remember from high school literature Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn” (“Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter…”). The urn probably looked like this, although not all urn scenes are bucolic. Two other examples I can think of comes from Browning, whose mastery of the dramatic monologue is closely related to the process of ekphrasis, and these are “Fra Lippo Lippi” (not the rock band), which is not just a poem about a painting but about the painter himself (a friar who was an artist), who is the speaker in the poem. Or, via another strategy, Browning’s more famous picture-poem, “My Last Duchess,” where the poet makes another character in the poem talk about a portrait of his “last” duchess. It is both an ekphrasis and a dramatic monologue. That's my last Duchess painted on the wall, /

Looking as if she were alive…” Why was she the “last”? Go back and read that poem. My other favorite is W.H. Auden’s “Musée de Beaux Art,” where something tragic is happening (Icarus falling out of the sky), while the unmindful world proceeds calmly on—the farmer farming, the ship sailing to its destination.

Now, if one had begun to read further into poetry and literature (as I did when I decided I wanted to become a poet), one would have found even more intriguing examples of ekphrasis. My other favorite is W.B. Yeat’s “Leda and the Swan.” Here is the poem in full.

A sudden blow: the great wings beating still

Above the staggering girl, her thighs caressed

By the dark webs, her nape caught in his bill,

He holds her helpless breast upon his breast.

How can those terrified vague fingers push

The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?

And how can body, laid in that white rush,

But feel the strange heart beating where it lies?

A shudder in the loins engenders there

The broken wall, the burning roof and tower

And Agamemnon dead.

Being so caught up,

So mastered by the brute blood of the air

Did she put on his knowledge with his power

Before the indifferent beak could let her drop?

The process was reversed when I wanted to cite “Leda…” as an example of ekphrasis in a literary posting in my blog. I tried to look for the painting that I remember best and which usually accompanied the poem or was referred to when I first read it. As you well know, it comes from the great Irish nationalist, classicist and modern poet, William Butler Yeats. I remember the ecstatic but averted face of Leda, the cottony white form of the swan between her legs. But I couldn’t find this painting on the Net, what I’m showing you now are several variations that I found through Google Images.

What intrigues me most, then and now as I read this poem again, is its images that take us back and forth through myth and history, and what specific events and actions in history (recorded in art) seem to have influenced, as the poem suggests, what became of the world and us, our civilization. Well, I couldn’t talk about the poem like this if I didn’t exert any effort to understand why, for example, a rape would be so important to a god. Thus I kept reading back and forth between the poem and its references (allusions, we used to call them in English class).

Let us therefore look a bit more closely at this this mythical rape, when a god (Zeus), a source and symbol power, forces himself upon a mortal (Leda). Yeats asks the questions about its consequences. What Yeats wrote here, I thought as a young man, hot-blooded more or less, were some of the most erotic lines in his huge overarching work: “her thighs caressed / By the dark webs… How can those terrified fingers push / The feathered glory from her loosening thighs?” ‘Thighs’, used twice here, I would like to point out, simply cannot be substituted by the prosaic ‘legs’, but just as the sonnet begins its sestet (it is Petrarchan), so too Yeats insinuates his crucial questions: “A shudder in the loins engenders there / The broken wall, the burning roof and tower / And Agamemnon dead.”

Critics identify two landmarks in Yeats’s poetic concept of history and how he comments on them: “The Second Coming” (Turning and turning the widening gyre / The falcon cannot here the falconer…), marks for him the end of modern history (maybe as distinguished for our contemporary times which Yeats could not have conceived) while “Leda and the Swan” seems to be a beginning—of the mythical, modern, Helenistic, age. The history that Leda and her offspring represent (sired by Zeus in the guise of a swan), who include Helen and Castor, unfolds for us the Trojan War (...Agamemnon dead), and the world in turmoil that came after it.

Watch, too, how Yeats had literally hung a line, breaking after “Agamemnon dead,” even if it had a period after it. Then he resumes, as though catching back the thought, through an indented fragment (actually a dependent clause) in the next line, “Being so caught up….” The effect that Yeats was after, I think, was to leave the thought of “Agamemnon dead…” hanging like the girl’s neck as the Swan violates her, “Being so caught up,” (finishing the line with a comma) in the divine will, yet so uncertain as to the consequences of it (ending with a question mark), which, it turns out, is rhetorical because we already know what happened to the world and to people after Leda’s offspring led the Greek civilization (and ours) to eventual ruin.

Yeats, like any poet of vision, saw the story of the world in the narrative of art. Art chronicles not just social or political history, but corresponds as well to the interior life of each man, race, nation, the internal or spiritual layer of the world, and the cosmos as man sees it. In much of Yeats’ work, like those of the poet-scholars that came after him, poetry is history.

Now for my personal experience. And you will have to allow me to use my own works as examples.

In the week after my good friend, your professor, Marj Evasco, and I ran into each other at the ceremonies of the Maningning Miclat Foundation’s poetry awards, I had a most interesting correspondence with the Sydney-based Filipino artist and writer Alfredo “Ding” Roces. Ding and I are members of an e-group called Banggaan (meaning, as we use it, collision, encounter,and interaction). It is an exuberant, chatty, gossipy assortment on the Web of professional and amateur artists, photographers, writers, and all sorts of good souls from the Philippines and the Filipino Diaspora. What the group does half-seriously and good-naturedly in the e-group is to post pictures or pictures of paintings and digital art, produced by the members, and afterwards there is an electronic free-for-all when all the other members send in any kind of comment, verse, or manipulate the pictures digitally. The result is a collection of strange shapes and visual amalgams, jokes, witticisms, doggerel, humorous verse. Banggaan counts among its members people like the musician Heber Bartolome, Austrialia-based cartoonist Edd Aragon, visual arts expert Ben Razon, Reuters photographer Claro Cortes and CNN’s Jaime Flor Cruz in Beijing, U.S.-based artists Melissa Nolledo-Christoffels, Glenn Bautista, and Rod Samonte.

Ding Roces, who had just won (again) a Manila Critics Circle National Book Award for his socio-historical book, Adios, Patria Adorada: The Filipino as Ilustrado, the Ilustrado as Filipino (De La Salle University Press), had also newly launched his blog, From My Cyberjournal. The blog is a veritable ore lode of interesting stories, reminiscences, and insights on various Philippine subjects, especially art, history and literature. An indubitable Renaissance Man, Ding (of the famous Roces family of writers, educators, publishers and one National Artist for Literature), is also a consummate editor and publisher, notably of the encyclopedic multi-volume Filipino Heritage series, which is sadly out of circulation now. Among other credentials, he is also the painter who studied under the former Dadaist, George Grosz.

And paintings (old ones “squirreled away” in boxes and recently unearthed), was what he put there in what appears his only his second blog posting. He had eight of them posted, some abstract, but old-fashioned me immediately gravitated towards the figurative ones. Here’s Sonatina.

My poem following is quite a unique case of ekphrasis, having undergone three transformations. First, it is Ding Roces who paints from a poem by Ruben Darío, the great Nicaraguan poet who was a favorite of his father’s, and Ding remembers the poem as he visits his apparently lovelorn niece studying at St. Theresa’s College in the 50s, after his stint with George Grosz in New York. He cajoles her into posing for him. The poem in Spanish had become a Filipino painting. You will agree with me that it is a most interesting painting. Then it becomes a poem, written by me, in English.

Sonatina

(from Ruben Darío and Alfredo Roces)

La princesa está triste... ¿Qué tendrá la princesa?

Los suspiros se escapan de su boca de fresa,

que ha perdido la risa, que ha perdido el color.

La princesa está pálida en su silla de oro,

... y en un vaso, olvidada, se desmaya una flor.

—Ruben Darío

The flower has become

A pair of broken straws, the vase

A soda bottle,

What gurgle of emptiness echoed,

When you sipped

The last drop of sweetened water?

Behind you, the gray

College, monastic in its bareness:

The nuns, so far

From your grief—what decades

Can they count

On the Sorrowful Mysteries?

Listen, the world is no longer

So simple. It is no respecter

Of tenderness. Ripening,

It crumples like a fruit.

Prepare yourself. Sorrows past

Are sorrows still to come.

(September 24, 2007)

Alfredo Roces’ “loose non-poetic translation” of the first stanza, which I used as epigraph, is thus: “The princess is sad...What ails her?

/ Sighs escape from her strawberry mouth

/ which has lost its laughter, which has lost its color

/ The princess sits pale in her golden chair

/ ...and in a vase, neglected, a flower swoons.”

What I’ve probably done, as I look back on it, is just to reconnect the painting to the original poem by pointing out what its images have become in the painter’s mind and in the actual situation of his subject. In the poem, the simple declarative opening, “The flower has become / A pair of broken straws…” does not conceal the fact that flowers becoming soft drink straws in an empty bottle is a rather is a rather unusual, even sinister, event.

The “gurgle of emptiness,” the “monastic bareness,” are both attempts to find what T.S. Eliot had called the “objective correlative,” the external equivalents of what perhaps was happening inside her who, like the princess in the original poem, sits lonely inside the nun’s cloister (the nuns who cannot even pray for her because her loneliness is unknown or unknowable to them, it is an impenetrable Sorrowful Mystery). While, outside, the whole world around her (a narrow strip of gray sky above the walls of the college), is threatening to crumble. There is something inconsolable about her as well as her “monastic” surroundings. The whole picture is one of archetypal sadness, originating from a long time before her, thus inevitable, and beyond her own powers to control. Even the poem does not seek to understand it.

These are my own thoughts about what I have done, which are no guarantee that you may undergo the same experience in reading the poem. If you do, I would be happy. Poets are seldom given that satisfaction.

I was having a writing binge (or feeding frenzy, you might call it) on Alfredo Roces’s paintings. I am actually building up a collection of ekphrastic studies on mainly Filipino paintings for a future book. Here is the second painting and its poem.

Recollections of Paradise

In my memory, green bottles

Meant oil or medicine kept by grandmothers

For that slight fever or bout

Of indigestion, perhaps from eating

Too many guavas filched from the neighbor’s tree

At the other side of the fence;

Or for that sprain after a rough game,

Or for herself, her swollen knees

And elbows: it meant a soothing liniment.

Or this bottle. Inside, a miniature

Tableau of the suffering Christ

And the grieving Mother (and John,

And the Magdalene?): Did he remember Paradise

Before he thought for a moment

He had been abandoned by the Father?

Or was it the Paradise he promised

The repentant thief whose copy

Is nowhere to be seen in this bottle?

We had similar bottles at the other altar

Grandmother kept in another part of the house,

Not at the main shrine of the Sacred Heart

That watched over our household.

They contained sacred oils blessed

By the Spanish priest at the Paschal hour,

(Beside the blackened statue of San Roque

With his faithful dog beside him,

A piece of bread in his mouth),

Old sacramentals like the faded novenas

Replaced by prayer books and scapulars

With words in English. We did not have

This icon bottle. I thought of guavas,

I see apples (and one glass marble),

In this Filipino Catholic still life. What

Have we replaced in our old faith?

What have we given up? A Paradise

Remembered in still another tongue,

Like our faith of Sundays,

Our innocence of catechumens,

The scent of apples, a game of marbles,

The liniment of holy oil that our grandmothers

Rubbed us with to hasten our convalescence?

What ails us? What is the name

Of our disease? Because we cannot utter it,

It is something we cannot conjure or cure.

It is the memory before this Paradise

That is the darkness of our soul.

(September 25, 2007)

I will not discuss this at length because it is a long poem, obviously. You can read it in your own good time, I prepared a hard copy of this small talk. Let me just describe the experience. It is no different from Marcel Proust’s petite madeleines. One taste of the magical muffins and memory’s floodgates open. Most poetry is like that, I think, you start with no particular plan or agenda (which might present itself in medias res), and you don’t know where it’s leading. My Catholic upbringing is just that—it is in the past, it is mainly subconscious, it is full of guilt and sadness. Which led me to this rumination. It is an unclosing of symbols, an examination of a conscience that is aware of the problems of faith and language, and that such problems may in fact be intertwined. I am reading my experience into the almost neutral (because it is not) still life by Alfredo Roces. He had assembled symbolic objects, and of course the symbolism is as variable as there are viewers. I almost didn’t know where the whole thing was leading to this until late in the writing.

The last poem is an even more surprising event. I couldn’t let go of the possibilities of images and language swirling in my mind. I went back to the Ding Roces blog and found I had completely missed one painting.

Man Dying

In this period I was interested in prehistoric cave paintings and was experimenting with some casein and rubber paints…. It was after I had read about this guy in East Berlin who was shot while making a break for the West Berlin border, collapsing somewhere in no man’s land separating the East from the West. The guards in the West could not, or would not, help him because he was not quite in West terrain, so he just lay there dying as guards and officials from both sides stared silently away.

—Alfredo Roces, From My Cyberjournal

At Lascaux, it was men crossing

The threshold of humanity,

Perhaps from a certain kind of death,

Into beauty.

Such shapes, indeed,

Of life, in muscle or shadow,

Shimmering in newfangled light

That was neither the sun’s nor the moon’s,

But struck from stones

And lit the eye that lead the hand

To line and color

that kept the ancient

Memory of these walls.

In Berlin, what threshold

Was almost crossed?

Only that of later men observing lines

And walls.

And what light

Lit the eye behind the cross-hairs

And moved the finger on the trigger,

And shut the eyes that stared

Silently away?

Only

That newfangled light that erases

Beauty with indifferent precision.

And yet this threshold was not

Precise (because no thresholds are).

It was the crossing

between

Caves where men lived

Only by their own newfangled lights

And thus drew precise lines

That shaped their own memories

And walls.

It was a crossing

Into the darkness

Before men lived in caves.

(September 28, 2007)

“Man Dying,” in Roces’ blog, had an extraordinary vignette, rising from the mists of the Cold War, part or which I used as epigraph, as you can see above. The painting spoke of more than political divisions, and the painting brought back pictures that had intrigued archaeologists and poets from the first time a cave decorated with Paleolithic paintings was discovered in Dordogne, France. Cirilo F. Bautista’s “Lascaux” is a favorite of mine. Even as I downloaded the piece, answered email or surfed, I was noting down lines, my mind was racing. I have my own memories of cave paintings, even if from books. They were the most fascinating things. And I have my own beef against intellectual arrogance—the notion, in individuals or nations, that no other ideas can be better than one’s own.

And it was the violence of the painting itself—man reduced to a flimsy primate, a primitive shape, entangled in barbed wire but almost diaphanous in its beauty as it almost blended into the texture of the medium itself (I looked up “casein” in the dictionary but it was of little help)—that reminded me of pictures of cave paintings (I have never been to Lascaux, not to mention France, like Cirilo has). We are intrigued by cave paintings because we see in them evidence of the advent of art—in people other than us, or who came before us, whom we thought were not capable of it. We admire them because we see how they were slowly becoming like us. The man dying in Berlin, etched on the cave wall of Roces’ canvas, is for me an evident warning of another Stone Age coming.

So. What is ekphrasis? My experience tells me it is a most stimulating, enjoyable manner of writing, especially poetry, from art. In fact it is not writing from painting only but from the other sister arts as well, as the title of your course says. What is important is how we discover possibilities, and how we use them, how we educe from one art another act of creation. I scoured the two encyclopedias I have, Britannica and Colliers, for a technical definition, but either my encyclopedias were not current or the word itself has lost currency, or not gained any currency at all. But although I am not an academic myself, I know it is a standard technical term in academe. The Internet was more helpful. The discussion blogs, the university sites, and even Wikipedia, had fairly substantial articles.

Ekphrasis is generally defined as the graphic, often dramatic description of a visual work of art. In ancient times it referred to a description of any thing, person, or experience. The word comes from the Greek ek and phrasis, out and speak respectively. The verb ekphrazein means “to proclaim or call an inanimate object by name.” Ah, not far from that familiar word, ‘expression’, is it not? Or, even from the naming of things, the casting of the magic spell that brought things into existence in language. So, perhaps Paradise was mute, that is, hidden, if not inexistent, before Adam and Eve uttered it? Was it violated—was its secret revealed—by language? Which seems obvious enough. Because language is always impure, and the Tree of Knowledge of is perhaps a family tree world languages, where all marriages are misalliances. Again let us leave that for another day.

Certainly ekphrasis is not a poetic form, like a sonnet or sestina or villanelle, but a rhetorical device “in which one medium of art tries to relate to another medium by defining and describing its essence and form, and in doing so, relate more directly to ‘you’, the audience through its illuminative liveliness.” To be lively (and illuminative), it must result from interaction. By nature, because two forms of art are in the end different entities, there is a distinct and extraordinary exchange of energy, mutually reinforcing or even competitive, that takes place between the two works of art. The interaction becomes a confrontation, a collision, as well as a collusion that gives birth to a new work. It is a manner of take-off, rather than only a deliberative process, or strategy, because it is also driven by instinctive, emotional power.

There are actually conventions of ekphrasis. Students and enthusiasts of the art identify and define almost a dozen ways of doing ekphrasis, but I have limited them to five (5) major ones (since the others may be considered sub-conventions):

1) Giving Voice to the painting or making its character or characters speak. Ex.: Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” and his poems mentioned above;

2) Praise, Response, with the poet or the persona praising the mastery of the work, or its stasis or permanence which is very different from the dynamism of a work made of words; or the poet, drawn to the work, goes through a deeply moving visual experience, he is “transfixed”; response may use descriptions of the painter’s actions, the situation or situations surrounding painting (in his studio, or in museum, etc.). Ex.: Auden’s “Musee de Beaux Arts,” and a lot of others;

3) Paragone Competition (da Vinci’s own term), where the poet competes or struggles with the painting either by pointing out its flaws or by critically differentiating his art of words from that of images; or by exhibiting his own learning about the artwork itself'; or, as in more modern examples, pointing out the inherent limits of either the artwork or language itself. Perhaps my poem “Man Dying” (since in it I wanted to “exhibit” my knowledge of Lascaux, in “competition” with the source of Mr. Roces’ painting);

4) Energy or “Enargia,” (from classical rhetoric) which is the natural vibrancy produced as the poet makes the artwork come to life before the reader’s eyes (painting with words); it is the same energy or vividness of experience that results from the poet’s struggle (the agon) with the artwork. Ex.: This is most exemplified in “Leda and the Swan”; and

5) Notional ekphrasis, may or may not belong to “real” ekphrasis because the object itself is imagined by the poet and he proceeds to write a poem about it, which is what Keats did with his (imaginary) Grecian urn; however, notional ekphrasis uses all the conventions of actual ekphrasis.

Definitions simply codify practice. We don’t have to be too technical about each them, they are not mutually exclusive. In practice they blend into each other. The examples are interchangeable. If you are more interested, many discussion sites cane found in the Internet. The conventions identified above are taken from http://calamity.wordherders.net/.

The practice is as old as poetry itself, and poets have been doing it since they first saw a sculpture or a painting that they liked. In more contemporary times, I think poets have always been looking out for art as take-off and inspiration, from Pound, Eliot, and Auden, to Jeffers, Lowell and Plath, from Bautista, Salanga, Abad, and Evasco, to Tinio, the two Antonios, and Rio Alma.

In addition, let me refer to A.S. Byatt, in her short critical work called Portraits in Fiction. She begins in this manner:

Portraits in words and portraits in paint are opposites, rather than metaphors for each other. A painted portrait is an artist’s record, construction, of a physical presence, with a skin of color, a layer of strokes of the brush, or the point, or the pencil, on a flat surface. A painting exists outside time and records the time of its making. It is in an important sense arrested and superficial—the word is not used in a derogatory way. The onlooker… may construct a relation in time with the painter, the sitter and the recorded face, but this is a more arbitrary, less consequential time than the end-to-end reading of a book.

I would like to think that A.S. Byatt might as well be talking about “portraits” in poetry, with “portrait” here meaning not just the painting of a head but the rendition, of a scene. (The word rendering, A.S. Byatt notes, was important then in the art criticism of the early 20th century.) “A portrait in a novel or a story,” A.S. Byatt continues, “may be a portrait of invisible things—thought processes, attractions, repulsions, subtle or violent changes in whole lives, or groups of lives….”

And so, ekphrasis—from images to words (from painting and the other non-verbal arts of sculpture, the graphic arts, and dance)—to poetry, not just interprets the subject, but re-invents it, renders it in the medium and metaphor of language, where shapes and textures—a human head, a Greek urn, a scene with a winged boy falling out of the sky, a graceful swan raping a girl, and all the “invisible things”—are words.

I would also like to think that you are here because you are or intend to be practitioners of the word. Poetry, according to Wordsworth, “slows us down.” It demands from us the consequential time that we need to contemplate life.

Invariably, we use language to confront daily life. We read product labels in supermarkets, we read contracts and road maps. Finding our way through daily life, or in strange places, is both a matter of survival and a cause for celebration.

The act is ekphrastic, which suspiciously sounds like ecstatic, which is what you feel when you have an epiphany. That is what I felt when I was writing these poems, and this little story. Which is what I hope you felt while listening to me.

Marne L. Kilates

(rev. October 3, 2007)

PAINTINGS: (from top) Breughel's Icarus, Rubens' Leda, and a Grecian urn. Alfredo Roces' Sonatina, Recollections of Paradise and Man Dying.

Home » Uncategories » Ekphrasis: Or, the Manner of Writing Poetry On, About, From & After Paintings & Other Non-Verbal Art